JOINTS 2026;

4: e1908

DOI: 10.26355/joints_20261_1908

Osteotomies around the knee for the treatment of varus knees with medial compartment osteoarthritis in patients aged over 65 years old – a systematic review

Topic: Osteotomy

Category: Systematic Review

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Osteotomies around the knee are well-known procedures in the management of unicompartmental joint overload, osteoarthritis, and ligament instability. Traditionally reserved for younger patients, the indications are becoming more inclusive, expanding also to elderly patients. However, only a few studies have evaluated the outcomes in this population. The aim of the present study is to assess the clinical outcomes, return to sport (RTS) rates, survival, revision rates and complications following knee osteotomies for the treatment of varus knee with medial compartment osteoarthritis in patients aged over 65 years.

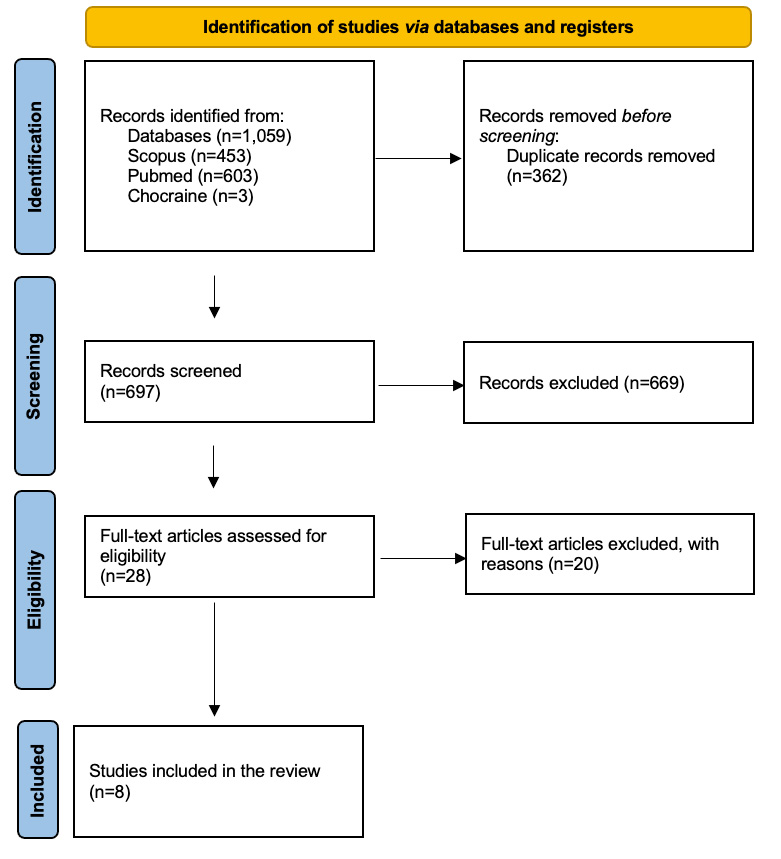

MATERIALS AND METHODS: A systematic review was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines and registered on PROSPERO. Studies providing clinical outcomes or survival rates in patients over 65 years old undergoing knee osteotomies for knee osteoarthritis were included. A total of 8 studies met the inclusion criteria. Demographics, follow-up, surgical technique, clinical scores, RTS, survival, revision rates, and complication rates were extracted from the included studies.

RESULTS: Clinical outcomes improved significantly postoperatively across all age groups. Patients ≥65 years achieved comparable results in terms of pain relief and satisfaction, despite slightly lower functional scores. RTS rates remained high, with a trend toward lower-impact activities. Survival rates at 10 years ranged between 70-95%, and complication rates were higher in elderly patients (23.1% vs. 15.7%), particularly for systemic diseases.

CONCLUSIONS: Knee osteotomies for varus knee with medial compartment osteoarthritis in patients over 65 years old result in satisfactory clinical outcomes and high RTS rates, representing a viable joint-preserving option in selected cases. Nonetheless, careful patient selection and preoperative counseling are essential due to increased risks of complications and slightly reduced survival rates compared to younger cohorts.

Introduction

Osteotomies around the knee are well-known procedures in the management of unicompartmental joint overload, osteoarthritis, and ligament instability. The indications are becoming more and more inclusive due to improvements in surgical technique and better understanding of lower limb alignment and forces acting on the knee joint1-3.

Osteotomies regained popularity in recent years, especially because they can preserve the knee and potentially delay or even avoid knee arthroplasty in selected patients. Moreover, advances in implant design and stability, deformity analysis, and patient-specific instrumentation (PSI) for complicated cases further increased their diffusion. Various studies4-7demonstrate a very good survival rate and clinical and radiographic outcomes when the osteotomy techniques are applied correctly with appropriate indications.

Historically, the “ideal” patient for an osteotomy presents with BMI <30, high functional demand (excluding running or jumping), unrestricted range of motion, and normal ligament balance, as a non-smoker and aged between 40 and 60 years old1. However, many of these limitations in indications have been questioned in recent years, including age. In fact, advanced age could be considered a risk factor for osteotomy failure, as it is associated with reduced bone healing capacity, increased joint stiffness, the presence of multiple comorbidities and lower functional demands8-11.

Nonetheless, due to worldwide population aging with elderly people requiring higher quality of life standards, osteotomies have been spreading among this age group as a procedure to better preserve knee function, delaying the need for an arthroplasty. Different studies2,12,13 show that age does not affect the radiological and clinical outcomes after an osteotomy procedure and comparable results are obtained at different ages in long-term follow-up. In addition, a recent ESSKA Consensus14 does not report a clear cutoff age value that limits the indication for an osteotomy, focusing more on the patient’s general status instead.

In this systematic review, we aim to present a thorough analysis of osteotomy outcomes for the treatment of varus knees with medial compartment arthritis in the older age population in order to provide further options in treating this increasingly widespread and demanding population. The primary aim is to evaluate clinical outcomes, return to sport (RTS) rates, survival, revision rates, and complications in osteotomies in patients ≥65 years old. The secondary aim is to compare, where available, these findings to outcomes reported in younger cohorts.

Materials and Methods

The current systematic review was performed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and is registered in the PROSPERO Registry (CRD420250633416) (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD420250633416)15,16.

Search Strategy

A systematic search was conducted in the PubMed (MEDLINE), Scopus and Cochrane Library databases on December 29, 2024. The following search terms were entered into the title, abstract, and keyword fields: (“high tibial osteotomy” OR “distal femoral osteotomy” OR “knee osteotomy”) AND (“knee joint” OR knee) AND (“older” OR “elderly” OR “elder” OR “65” OR “70” OR “75” OR “80”) AND (“arthritis” OR “osteoarthritis”).

The inclusion criteria were studies published providing clinical outcomes or survival rates in patients over 65 years old undergoing knee osteotomies for knee osteoarthritis. Studies conducted using randomized controlled trials, controlled (non-randomized) clinical trials, prospective and retrospective comparative cohort studies, case-control studies, and case series were included.

The exclusion criteria were non-English language papers and studies that did not provide clear clinical results. Studies with combined procedures with knee osteotomies [e.g., anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) reconstruction] were excluded, as well as studies involving heterogeneous treatments (e.g., knee osteotomies and unicompartmental knee replacement). Case reports, reviews of the literature, letters to editors, biomechanical reports, ex vivo or cadaveric studies and editorial commentaries were excluded as well.

Data Collection

The retrieved articles were first screened by two of the authors (A.M. and G.A.) by title and, if found relevant, screened further by reading the abstract. After excluding studies not meeting the eligibility criteria, the entire content of the remaining articles was evaluated for eligibility. To minimize the risk of bias, the authors reviewed and discussed all the selected articles, references, and articles excluded from the study. In case of any disagreement between the reviewers, one of the senior authors (G.C.) made the final decision. At the end of the process, further studies that might have been missed were manually searched by going through the reference lists of the included studies and relevant systematic reviews.

The data were extracted from the selected articles by two of the authors (A.M. and G.A.). Each article was validated again by the senior author before analysis. For each included study, the following data were extracted: number of patients, patient demographics (age, sex, body mass index), year of treatment, study design, follow-up, surgical technique, and type of osteotomy. Clinical outcome measures, return to sport data, survival and revision rates, and reported complications were also recorded. Additionally, the severity of osteoarthritis was extracted when available. The Oxford Levels of Evidence set by the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine were used to categorize the level of evidence17. The quality of the selected studies was evaluated using the Methodological Index for Nonrandomized Studies (MINORS) score18. The checklist consists of 12 items, of which the last four are specific for comparative studies. Each item could be scored from 0 to 2 points. The ideal score was set at 16 points for non-comparative studies and 24 for comparative studies.

Data Analysis

Data were qualitatively synthesized due to the heterogeneity of study designs, outcome measures, and statistical reporting. Meta-analysis was not performed. Clinical and functional outcomes were compared descriptively across studies reporting both mean and standard deviation. Where applicable, p-values were reported to indicate statistical significance. Return to sport data were summarized by reporting RTS rates and average Tegner scores. The survival analysis was discussed separately. Microsoft Excel (version 16.63, Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) was used for data management and graphical representation.

Results

The electronic search yielded 1,059 studies. After 362 duplicates were removed, 697 studies remained, of which 669 were excluded after reviewing the abstracts, bringing the number down to 28. Subsequently, 20 additional articles were excluded after full-text reading based on the aforementioned inclusion and exclusion criteria. No additional studies were found by manually searching the reference lists of the selected articles. Finally, 8 studies2,8,9,12,13,19-21 met the inclusion criteria and were included for further analysis (Figure 1). The studies analyzed had an average MINORS score of 19.9 (SD 4.39), indicating the methodological quality of the available literature.

Study Characteristics

A total of 8 studies2,8,9,12,13,19-21 met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final analysis. All patients and study characteristics are reported in Table 1. The studies included were retrospective comparative studies, cohort studies, and case series.

A total of 61,741 patients (corresponding to 61,774 knees) were included. Overall, 6,426 patients were ≥65 years old (6,441 knees), and 55,222 were <65 years old (55,237 knees), with a mean age of 70.2 years for patients ≥65 years and 52.7 years for patients <65 years. The mean follow-up was 41.8 months (range: 11.9 – 120 months) for patients ≥65 years and 42.9 months (range: 11.8 – 120 months) for patients <65 years.

Of them, Lee et al8, in a retrospective cohort study based on database analysis, contributed the majority of the total sample with 61,145 patients, of whom 6,138 were over 65 years old. This study exclusively reported implant survival and revision rates, without including functional or clinical outcome measures. The remaining seven studies included a total of 596 (629 knees) patients, of whom 523 were aged ≥65 years, and focused on clinical outcomes, return to sport (RTS), and complications.

The included studies employed different surgical techniques: open wedge high tibial osteotomy (OWHTO) in six studies2,8,13,19-21 and closing wedge high tibial osteotomies (CWHTO) in two studies9,12.

The studies were conducted across different countries, including Japan, Korea, Austria, and the United States, reflecting a variety of clinical practices and patient populations.

Clinical Outcomes

Clinical outcomes were reported in six studies2,12,13,19-21 (Table 2). A total of 523 patients were included: 259 patients <65 years (mean age 56.7 years) and 264 patients ≥65 years (mean age 70.8 years), with mean follow-up of 28.7 months and 30.2 months, respectively.

Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) score

The JOA score was assessed in one study. Goshima et al2 found that patients <65 years achieved a mean score of 90.9 (SD 8.7), compared to 86.7 (SD 8.2) for those ≥65 years.

Oxford Knee Score (OKS)

OKS was presented by Goshima et al2, showing similar outcomes between groups: 41.4 (SD 5.9) for patients <65 years and 41.6 (SD 5.9) for those ≥65 years (p=0.89).

Knee Society Score (KSS)

KSS was assessed in two studies. Kuwashima et al12 found that the functional activities score was significantly lower in patients ≥65 years than in those <65 years (p=0.011). Otoshi et al20 reported KSS scores of 87.1 (SD 8.3) for patients <70 years and 82.8 (SD 10.0) for those ≥70 years (p=0.09), with improvement in both groups.

LYSHOLM score

Lysholm scores were provided by Nakashima et al21, Park et al13, and Kamada et al19. Nakashima et al21 recorded scores of 89.0 (SD 8.5) for patients <70 years and 87.7 (SD 11.9) for those ≥70 years (p=0.58). Park et al13 observed similar outcomes with 54.9 (SD 15.1) in patients <55 years and 51.5 (SD 19.8) in patients ≥65 years. Kamada et al19 reported a significant improvement from 60.8±8.9 preoperatively to 92.5±2.5 postoperatively (p<0.0001).

International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC)

Only Park et al13 reported the IKDC score. Patients <55 years old exhibited an IKDC score of 54.9±15.1 and 51.5±19.8 in patients ≥65 years old, with no significant difference.

In summary, clinical outcomes improved significantly across all age groups, with no significant differences among patients under or over 65 years old. Patients <65 years showed higher functional scores, while patients ≥65 years demonstrated comparable improvements in satisfaction and symptom relief.

Return to Sport

Two studies19,20 reported outcomes on RTS (Table 3). A total of 124 patients (147 knees) were included: 78 patients (100 knees) were ≥65 years, and 36 patients (36 knees) were <65 years, with mean follow-up periods of 50.7 months and 48.2 months, respectively.

RTS rates were high across both age groups. Otoshi et al20 observed RTS rates of 96.0% in patients <70 years and 91.2% in patients ≥70 years. Moreover, they observed that among patients <70 years, 66.7% returned to the same sport level and 33.3% at a lower level. On the other hand, 74.2% of the patients of the older group returned to the same level, 22.6% at a lower level, and 3.2% at a higher level. An overall shift to lower-impact sports was observed20. Kamada et al19 reported that 11 patients (19.6%) improved their sports activity following surgery.

The Tegner activity scale was presented by Otoshi et al20. This score decreased postoperatively compared to preoperative levels, with mean postoperative scores of 3.3±1.4 for patients <70 years and 2.7±1.2 for those ≥70 years. The difference was not statistically significant (p=0.16)20.

In summary, both studies demonstrated high RTS rates following surgery, with older patients achieving satisfaction levels comparable to those of younger patients despite a shift toward lower-impact activities.

Survival and Revision Rates

Five studies2,8,9,12,13 reported survival rates and complications (Table 4). A total of 61,645 patients were included: 55,222 patients <65 years and 6,423 patients ≥65 years, with a mean follow-up of 9.8 years for patients <65 years and 10.7 years for patients ≥65 years.

Trieb et al9 reported 90% survival at 10 years for patients <65 years and 70% for those ≥65 years. Moreover, the risk of failure increased significantly with age, rising by 7.6% for each additional year. Patients aged 65 or older had a significantly higher failure rate compared to younger patients (38.4% vs. 23.1%; p=0.0381), with a relative risk of 1.55 (95% CI: 1.01-2.38; p=0.0461).

Kuwashima et al12 observed survival rates of 99.3% at 5 years, 95.1% at 10 years, and 85.5% at 15 years for patients ≤64 years, while the rates for patients ≥65 years were 98.6%, 93.3%, and 83.3%, respectively. There was no significant difference between the two groups for the survival rate after high tibial osteotomy (HTO) (p=0.602).

Park et al13 recorded a 95.2% survival rate at 4 years for patients ≥65 years. However, in the older group, there were 7 cases (11.3%) of conversion to total knee arthroplasty (TKA), while no conversions were reported in the younger group (p=0.007). Lee et al8, analyzing a large cohort of 61,145 patients, reported a low revision rate in all age groups. This study alone contributed over 99% of the total sample for the survival analysis, making it the primary source of long-term survival data in this review. Nonetheless, revision rates were significantly lower in patients <60 years (4.1% at 10 years) than in those >60 years (7.32% at 10 years) (p<0.001)8.

Complications

Data are reported in Table 4. The incidence of perioperative complications reported by Lee et al8 was higher in patients aged ≥65 years than in those aged 60-65 or <60 years. Specifically, older patients (>65) had an increased risk of medical complications such as pulmonary thromboembolism (HR 1.97), cerebrovascular accident (HR 1.55), myocardial infarction (HR 1.52), acute respiratory failure (HR 2.24), and delirium (HR 2.57). Additionally, the rate of surgical site infections was significantly higher in the oldest group (HR 1.61) (p=0.001)8.

Goshima et al2 reported overall complication rates of 23.1% in patients ≥65 years and 15.7% in those <65 years, but these differences were not statistically significant. The types of complications observed included delayed union (2 in older vs. 1 in younger patients), infection (1 vs. 2), screw head breakage (2 vs. 3), and complex regional pain syndrome (1 case in the older group).

In summary, while both studies agree that overall complication rates tend to be higher in older patients, the type of complications differs: older patients are more prone to systemic medical complications, whereas mechanical issues (e.g., nonunions, hardware problems) occur across all ages2.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review that directly evaluates outcomes and survival rates in patients aged over 65 years old undergoing knee osteotomy.

The key findings of this research indicate that age over 65 years old does not significantly influence clinical outcomes in patients undergoing a knee osteotomy for a varus knee with medial compartment osteoarthritis compared to younger patients.

Indeed, previous studies22-24 reported that age does not affect clinical outcomes. However, most of the studies were conducted on cohorts of young patients. Clinical outcomes on elderly patients (≥65 years old) compared with younger groups are investigated in 6 studies from 2015 to 2024, which were included in the present review2,12,13,19-21. The findings revealed that older patients seem to have comparable clinical outcomes in terms of symptom relief, satisfaction, and fulfillment of pre-operative expectations. For example, Goshima et al2 found that a patient aged ≥65 years had JOA scores and OKS scores comparable to those of younger patients. Similarly, Kuwashima et al12 reported that, at a mean follow-up of 11.4 years, KSS symptom score, KSS satisfaction score, and KSS expectation score were comparable between the younger and older groups. Consistent findings were also reported in another cohort study from Park et al13.

These findings were further supported by radiographic assessments, which demonstrated comparable post-operative alignments between groups, as measured by parameters such as the hip-knee-ankle (HKA) angle, posterior tibial slope (PTS), Insall-Salvati ratio, and weight-bearing line orientation13. Post-operative alignment is a key factor influencing clinical outcomes, as highlighted by Hohloch et al25, who reported that achieving the planned varus/valgus correction is associated with improved pain relief and functional recovery.

Nonetheless, older patients reported lower functional recovery compared to younger patients, whereas satisfaction and symptom relief were comparable. Data reported in our review indicate that the KSS function score was statistically lower in people older than 65 years old. However, Otoshi et al20 reported similar outcomes in both age groups (<70 and >70 years) within a cohort with a mean age of 68 years, when comparing the KSS functional score. They also found that pre-operative Tegner activity scale was lower in the older age group, and that the overall post-operative Tegner score remained lower among all patients20. These findings suggest that HTO can still provide good functional outcomes in older patients. However, their pre-operative functionality and fitness levels tend to be lower than those of younger patients, and this difference generally persists post-operatively, despite significant improvements in symptoms and functional scores.

Nowadays, elderly patients maintain an interest in sport-related activities; therefore, RTS should be considered an important factor when evaluating post-operative satisfaction26. In the studies included in the present review, patients over 65 achieved RTP rates comparable to those of younger patients, although with a shift toward lower-impact activities. Kamada et al19 performed a study on sports and physical activities (SPA) in elderly patients to investigate the patient ratio that maintains SPA post-operatively. Eleven patients (19.6%) improved their sport activity following surgery; however, the overall ratio of patients returning to SPA at the same, higher, or lower level remained below 30% in patients older than 65 years old (mean age 71 years old), a percentage comparable to the pre-operative rate. All data were collected at a 14-month follow-up. According to Otoshi et al20, patients older than 70 years old achieved high RTS (91%), with 77% of patients returning at the same or higher level at 32.9 months of follow-up, even though returning mostly to low-impact activities. Moreover, seven patients began participating in sports activities for the first time after surgery20. The lower follow-up period in Kamada et al19 study could be a confounding factor, suggesting that RTS rates among elderly patients could have a higher incidence than expected.

This result may be explained by the improvement in techniques and fixation devices that allow early weight bearing and, therefore, promote faster rehabilitation and reduce muscle weakness. Rehabilitation is indeed a critical factor, especially for older patients27-29. These results are consistent with other studies30,31 conducted in younger populations, which also report high RTP rates after knee osteotomy.

RTS after HTO should be compared to RTS after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA), as these procedures are frequently proposed to a similar middle-aged cohort of patients. According to Radhakrishnan et al32, the RTS rate after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) exceeded 90% at 48 months follow-up. However, the mean age in that study was 51.8 years, significantly younger than the population considered in our review. Belsey at al33 compared RTS rates after HTO and UKA, reporting no significant differences in RTS rates among groups. With a mean age of 48.4 years old and 60.6 years old, respectively, further studies are needed to provide a better age-normalized comparison among these groups, as HTO could lead to significantly higher RTS when the same age groups (older than 65-70 years) are compared33.

Despite the overall good functional results reported in the present review for the older age group, age appears to significantly influence survival and revision rates. Most of the studies concur in reporting higher failure rates among older patients (≥65 years old)8,12,13. Interestingly, the revision rates observed in these older populations are comparable to those reported in the literature for younger cohorts (<55 years). In fact, several studies34-36 have documented survival rates of approximately 95%, 86%, and 94% at follow-ups ranging from 10 to 15 years, indicating that acceptable long-term outcomes can still be achieved in well-selected elderly patients.

One study included in this review reported a significantly higher incidence of perioperative complications in older patients8. In fact, Lee et al8, observed a higher incidence of medical complications such as pulmonary thromboembolism, cerebrovascular accident, myocardial infarction, acute respiratory failure, and delirium, and a higher risk of surgical site infections8. Given the exceptionally large sample size included in this study, these findings carry substantial weight in the overall interpretation of perioperative risks in older patients undergoing knee osteotomy.

In contrast, Goshima et al2 found a similar complication rate among the patient groups investigated. Notably, while both studies agree that complication rates tend to be higher in older patients, the nature of these complications appears to differ. Older patients are more prone to systemic medical complications, whereas mechanical issues – such as hinge fractures, nonunion, and hardware-related problems – occur across all age groups. This may be attributed to the higher prevalence of comorbidities among elderly patients. Underlying conditions such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, peripheral vascular disease, and diabetes mellitus are more common in this population34.

These findings underscore the importance of careful patient selection and thorough preoperative risk stratification when considering osteotomy in elderly individuals. Patients older than 65 years old must be thoroughly informed about the increased risk of failure and complications.

The present review has several limitations. First, patient groups were not consistent across studies, as different cutoff values were used; some studies defined older patients as those over 65 years, while others adopted 70 years as the threshold. Second, not all studies assessed the same clinical outcomes and scoring system, making clinical outcomes related to satisfaction and expectations not entirely comparable. Lastly, while clinical outcomes were derived from small-to-moderate cohort studies with detailed follow-up, survival data largely stem from one large database study8, which may introduce a distinct bias related to administrative coding and less detailed functional evaluation.

Conclusions

Elderly patients aged more than 65 years old with medial compartment osteoarthritis and varus knee can achieve predictable pain relief, satisfaction, and good clinical outcomes after knee osteotomies. However, studies highlighted a trend of having lower functional scores, which may reflect their preoperative activity levels. Return to sport rates remain high, even though there is a shift toward lower-impact activities.

While knee osteotomies may represent a joint-preserving option in selected patients aged over 65 years old, they should be carefully counseled about the higher (although acceptable) risk of failure and the lower survival rate with respect to the younger age groups.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Funding

The study was not supported by any source of funding.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this manuscript.

AI Disclosure

During the preparation of this work, the authors did not use any AI or AI-assisted technologies to improve the scientific work.

Authors’ Contributions

Substantial conception/design of work (G.C., A.M.), data collection (G.C., A.M., G.A. and M.S.), interpretation of data (G.C., A.M., and A.M.), drafting the work (A.M. and A.M.), critically revising the work (G.C., B.T., M.C., L.M., C.R.), manuscript preparation (G.C., A.M. and A.M.), approving final version for publication (all authors), and agreement for accountability of all aspects of work (all authors). All authors have read and approved the final submitted manuscript.

References

- Brinkman JM, Lobenhoffer P, Agneskirchner JD, Staubli AE, Wymenga AB, Van Heerwaarden RJ. Osteotomies around the knee: patient selection, stability of fixation and bone healing in high tibial osteotomies. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008; 90: 1548-1557.

- Goshima K, Sawaguchi T, Sakagoshi D, Shigemoto K, Hatsuchi Y, Akahane M. Age does not affect the clinical and radiological outcomes after open-wedge high tibial osteotomy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2017; 25: 918-923.

- Kayaalp ME, Apseloff NA, Lott A, Kaarre J, Hughes JD, Ollivier M, Musahl V. Around-the-knee osteotomies part 1: definitions, rationale and planning—state of the art. J ISAKOS 2024; 9: 645-657.

- Staubli AE, De Simoni C, Babst R, Lobenhoffer P. TomoFix: a new lcp-concept for open wedge osteotomy of the medial proximal tibia – early results in 92 cases. Injury 2003; 34: 55-62.

- Dorsey W, Miller B, Tadje J, Bryant C. The stability of three commercially available implants used in medial opening wedge high tibial osteotomy. J Knee Surg 2010; 19: 95-98.

- Virolainen P, Aro HT. High tibial osteotomy for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a review of the literature and a meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2004; 124: 258-261.

- Murray R, Winkler PW, Shaikh HS, Musahl V. High tibial osteotomy for varus deformity of the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev 2021; 5: e21.00141.

- Lee SH, Seo HY, Kim HR, Song EK, Seon JK. Older age increases the risk of revision and perioperative complications after high tibial osteotomy for unicompartmental knee osteoarthritis. Sci Rep 2021; 11: 24340.

- Trieb K, Grohs J, Hanslik-Schnabel B, Stulnig T, Panotopoulos J, Wanivenhaus A. Age predicts outcome of high-tibial osteotomy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2006; 14: 149-152.

- Bouguennec N, Mergenthaler G, Gicquel T, Briand C, Nadau E, Pailhé R, Hanouz JL, Fayard JM, Rochcongar G; Francophone Arthroscopy Society. Medium-term survival and clinical and radiological results in high tibial osteotomy: factors for failure and comparison with unicompartmental arthroplasty. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2020; 106: S223-S230.

- Keenan OJF, Clement ND, Nutton R, Keating JF. Older age and female gender are independent predictors of early conversion to total knee arthroplasty after high tibial osteotomy. Knee 2019; 26: 207-212.

- Kuwashima U, Okazaki K, Iwasaki K, Akasaki Y, Kawamura H, Mizu-Uchi H, Hamai S, Nakashima Y. Patient reported outcomes after high tibial osteotomy show comparable results at different ages in the mid-term to long-term follow-up. J Orthop Sci 2019; 24: 855-860.

- Park JY, Kim JH, Cho JW, Kim MS, Choi W. Clinical and radiological results of high tibial of osteotomy over the age of 65 are comparable to that of under 55 at minimum 2-year follow-up: a propensity score matched analysis. Knee Surg Relat Res 2024; 36: 10.

- Dawson M, Elson D, Claes S, Predescu V, Khakha R, Espejo-Reina A, Schröter S, van Heerwarden R, Menetrey J, Beaufils P, Seil R, Becker R, Mabrouk A, Ollivier M. Osteotomy around the painful degenerative varus knee has broader indications than conventionally described but must follow a strict planning process: ESSKA Formal Consensus Part I. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2024; 32: 1891-1901.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021; 372: n71.

- Sideri S, Papageorgiou SN, Eliades T. Registration in the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) of systematic review protocols was associated with increased review quality. J Clin Epidemiol 2018; 100: 103-110.

- DiSilvestro, KJ, FP Tjoumakaris, MG Maltenfort, KP Spindler, KB Freedman. Systematic reviews in sports medicine. Am J Sports Med 2016; 44: 533-538.

- Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg 2003; 73: 712-716.

- Kamada S, Shiota E, Saeki K, Kiyama T, Maeyama A, Yamamoto T. Sports and Physical Activities of Elderly Patients with Medial Compartment Knee Osteoarthritis after High Tibial Osteotomy. Prog Rehabil Med 2017; 2: 20170006.

- Otoshi A, Kumagai K, Yamada S, Nejima S, Fujisawa T, Miyatake K, Inaba Y. Return to sports activity after opening wedge high tibial osteotomy in patients aged 70 years and older. J Orthop Surg Res 2021; 16: 576.

- Nakashima M, Takahashi T, Matsumura T, Takeshita K. Postoperative improvement in patient‐reported outcomes after neutral alignment medial open wedge high tibial osteotomy for medial compartment knee osteoarthritis in patients aged ≥70 years versus younger patients. J Exp Orthop 2024; 11: e12035.

- Floerkemeier S, Staubli AE, Schroeter S, Goldhahn S, Lobenhoffer P. Outcome after high tibial open-wedge osteotomy: a retrospective evaluation of 533 patients. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013; 21: 170-180.

- Kohn L, Sauerschnig M, Iskansar S, Lorenz S, Meidinger G, Imhoff AB, Hinterwimmer S. Age does not influence the clinical outcome after high tibial osteotomy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013; 21: 146-151.

- Ruangsomboon P, Chareancholvanich K, Harnroongroj T, Pornrattanamaneewong C. Survivorship of medial opening wedge high tibial osteotomy in the elderly: two to ten years of follow up. Int Orthop 2017; 41: 2045-2052.

- Hohloch L, Kim S, Mehl J, Zwingmann J, Feucht MJ, Eberbach H, Niemeyer P, Südkamp N, Bode G. Customized post-operative alignment improves clinical outcome following medial open-wedge osteotomy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2018; 26: 2766-2773.

- Nakamura R, Takahashi M, Shimakawa T, Kuroda K, Katsuki Y, Okano A. High tibial osteotomy solely for the purpose of return to lifelong sporting activities among elderly patients: a case series study. Asia Pac J Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Technol 2020; 19: 17-21.

- Schröter S, Ateschrang A, Löwe W, Nakayama H, Stöckle U, Ihle C. Early full weight-bearing versus 6-week partial weight-bearing after open wedge high tibial osteotomy leads to earlier improvement of the clinical results: a prospective, randomised evaluation. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2017; 25: 325-332.

- Takeuchi R, Ishikawa H, Aratake M, Bito H, Saito I, Kumagai K, Akamatsu Y, Saito T. Medial opening wedge high tibial osteotomy with early full weight bearing. Arthroscopy 2009; 25: 46-53.

- Bautmans I, Van De Winkel N, Ackerman A, De Dobbeleer L, De Waele E, Beyer I, Mets T, Maggio M. Recovery of muscular performance after surgical stress in elderly patients. Curr Pharm Des 2014; 20: 3215-3221.

- Liu JN, Agarwalla A, Garcia GH, Christian DR, Redondo ML, Yanke AB, Cole BJ. Return to sport following isolated opening wedge high tibial osteotomy. Knee 2019; 26: 1306-1312.

- Hoorntje A, Kuijer PPFM, van Ginneken BT, Koenraadt KLM, van Geenen RCI, Kerkhoffs GMMJ, van Heerwaarden RJ. Prognostic factors for return to sport after high tibial osteotomy: a directed acyclic graph approach. Am J Sports Med 2019; 47: 1854-1862.

- Radhakrishnan GT, Magan A, Kayani B, Asokan A, Ronca F, Haddad FS. Return to Sport After Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Orthop J Sports Med 2022; 10: 23259671221079285.

- Belsey J, Yasen SK, Jobson S, Faulkner J, Wilson AJ. Return to Physical Activity After High Tibial Osteotomy or Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review and Pooling Data Analysis. Am J Sports Med 2021; 49: 13721380.

- Alsuwaidan S. Prevalence of comorbidity among elderly. Glob J Aging Geriatr Res 2021; 1.

To cite this article

Osteotomies around the knee for the treatment of varus knees with medial compartment osteoarthritis in patients aged over 65 years old – a systematic review

JOINTS 2026;

4: e1908

DOI: 10.26355/joints_20261_1908

Publication History

Submission date: 16 Apr 2025

Revised on: 18 Jun 2025

Accepted on: 26 Jan 2026

Published online: 09 Feb 2026